Faith Beyond Words

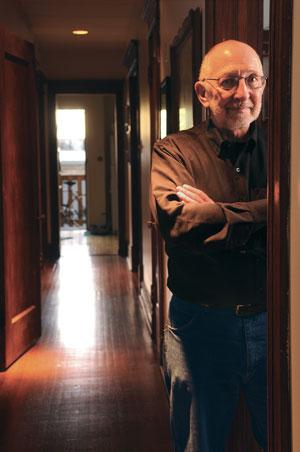

Lloyd DeGrane

Greg Dell

There are days when Greg Dell can’t speak for anyone. Days that his words are too soft, too breathy, too slurred or too slow for anyone to understand. And on those days, he knows he has to be patient and wait until the speech muscles weakened by Parkinson’s disease allow him to form words again.

That silence is particularly painful for a man who’s spent almost 50 years of his life speaking out for those whom society has marginalized. It all started when he was 13 years old, sitting in a cold, hard pew, listening to a Methodist pastor make his parishioners squirm by telling them they had to take a stand on racism if they were true Christians.

Although his father, an Italian immigrant, wanted nothing more than for his family to blend into their white, blue-collar village of Midlothian, Ill., his son decided to follow his pastor’s words and take a stand.

In high school, he marched behind Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. through a white Chicago suburb, a place where people would normally smile and wave at him from their porches. But on that day, they shouted, spit and tossed rocks, one man running toward him waving an ax handle.

“That was a life-changing experience, that march,” the 62-year-old retired Methodist minister says quietly while sitting in a recliner, hands folded in his lap.

Dell also remembers the support his father, a police chief, gave him even on those frequent occasions when they disagreed. Politics never got in the way of family.

He enrolled at Illinois Wesleyan in 1963, choosing the school because of the financial support it offered. As a religion and philosophy major, he found college life exciting. “A lot of questions I had about the Christian faith I was able to toss out there without losing the baby with the bathwater because of some very good academic instructors. Wesleyan helped strengthen my faith by giving me the tools to see that Christianity could be intellectually sound. To be a Christian I didn’t have to throw out my brain in order to believe,” he says.

In college, Dell continued to devote himself to progressive causes. After he discovered that only seven black students were enrolled at Wesleyan, he joined most of those students, along with some of his white peers, in raising the matter with administrators. After being told that few African-Americans applied for admission, Dell’s group received those administrators’ consent to promote IWU among high-schoolers on Chicago’s South Side.

When a large bank that had loaned money to South Africa’s apartheid government was invited to recruit on campus, Dell joined another student group threatening an organized protest. The bank cancelled its visit, much to the dismay of Oliver Luerssen, then chair of Illinois Wesleyan’s Business Department.

“That made me real popular with him,” Dell says, smiling. “We had a 30-year discussion on that” – a debate made possible by the fact that the business professor would become his father-in-law (Luerssen died in 1992).

Dell met Jade Luerssen when they both showed up the first hour of the first day for freshman English in the wrong classroom. They dated off and on and married in August 1967 before heading to Duke University, where he studied for his master’s in divinity and she pursued a graduate degree in religious education, joining him as a full partner in his activism.

“I had these feelings of injustice in the world starting in high school but I didn’t know how to interpret them or what to do with them,” Jade says. “I learned that from Greg.”

And so did others, like the Rev. Vernice Thorn, an African-American, Methodist pastor who met Dell when she was a seminary student, placed in the Broadway United Methodist Church in Chicago where Dell served from 1995 to 2007. She had no idea his church was in the heart of a large gay community.

“When I got here and found out that a lot of the work that Greg was doing was around same-sex couples and a lot of the congregation was gay, it was kind of shocking,” she says. “But then almost immediately, with the passion Greg has for inclusivity, it just felt like I was in the right place at the right time.”

The first time she listened to him preach in the small, brick church, he talked about celebrating all of God’s people, speaking directly to gays, lesbians, blacks and whites.

“For the first time in my life, I heard a black woman was valuable,” Thorn says. “No one had ever explicitly said that to me. My soul just needed to hear it and that was a transforming moment for me.”

If there’s one word to describe Dell’s life, a word that surfaces in conversations with those who know him, it’s inclusion. He has a passion for embracing and advocating for all of humanity, which has led to multiple arrests for civil disobedience.

“Everybody I’ve debated, everybody I’ve confronted, every time I’ve been arrested, I’ve been scared, a lot of times angry, but almost always willing to confront,” Dell says.

His stand against U.S. involvement in Nicaragua and El Salvador led Dell to declare his pastorate at the time, Wheadon United Methodist Church in Evanston, a sanctuary for Central American refugees who were not legally allowed into the country. In 1986, he was arrested for chaining himself to the entrance of the United Methodist Church’s Board of Pensions office in Evanston to protest the board’s holdings in firms that did business with South Africa.

But two decades of marches, protests and arrests didn’t push him into the national headlines. That happened when a complaint was filed against Dell after he performed a service of holy union for two gay men in September 1998 at the Broadway church. The complaint stated that Dell had violated a recently adopted rule forbidding United Methodist ministers to conduct same-sex ceremonies. A call from the bishop followed. If he promised to never do it again, the complaint would go away. Dell couldn’t do that.

“I’d been doing wedding celebrations for gay and lesbian couples for 18 years and I just did them because two people wanted to affirm in a faith community their love for each other as a gift from God,” he says. “Thirty percent of my church was gay. What was I supposed to say, ‘I’ll take your money, I’ll baptize your babies, but I can’t marry you if you love each other’?”

After being formally charged with violating the same-sex union ban, Dell was tried by a jury of 13 Methodist ministers in March 1999. During the closely watched trial, Dell argued that his ordination vows to serve his congregation took precedence over church rules. Stephen Williams, a Methodist pastor who served as prosecutor in the case, countered that “the Church has the right to define and hold to its teachings and to ask its pastors to stay within those boundaries.”

A jury of 13 voted 10 to 3 to suspend him indefinitely, making him the first Methodist minister in the U.S. to be penalized for the violation. But the suspension would be lifted if he pledged not to do it again. Again he refused.

On appeal, the suspension was changed to one year, which sent him back to the Broadway church pulpit in 2000, where he continued blessing gay couples but in a way that didn’t violate church doctrine.

“I know no one else who’s as articulate as he is on issues of theology and social justice,” says Rev. Lynn Pries of Naperville, who’s known Dell for 30 years. “He’s just an extraordinary person with extraordinary gifts. He’s somebody who takes his faith seriously, even when it means a great cost to him personally.”

Throughout his trials with the church, Dell never stepped back, Pries says, even openly admiring those opposing him. Although he’s marched against racism and gender issues, exploitation and greed, “the one he’s really taken to heart and been most forceful on is the issue of inclusion.”

Life returned to normal for Dell for the next six years, until July 2006, when he was seeing his doctor for high blood pressure and mentioned a slight tremor in his hand. A neurologist diagnosed it as Parkinson’s disease. During a second opinion, he started to cry halfway through the testing. The doctor stopped, telling him Parkinson’s can make you more emotional.

But the pastor has always been emotional.

The doctor asked him to write a sentence and he couldn’t read his own handwriting.

Stress aggravates the crippling degenerative disease; he knew he had to reduce his 80-hour weeks. In a wrenching service, he told the congregation and the grieving began. He planned to deliver his last sermon Easter Sunday 2007.

That morning he woke up stuttering so badly he could hardly understand himself.

“I wanted to come back and preach one more time,” he says, almost in a whisper, his eyes filling.

Long-time parishioner Arlie Sims of Chicago said that accepting Dell’s suspension for his beliefs was easier than accepting the disease.

“When he left because of the trial, there was kind of a clear focus for our anger and our hurt and that was unjust policies within the denomination, but when he got Parkinson’s, who do you blame?”

“No one” would be Dell’s answer. One of the lessons he still teaches is that God is not the author of suffering. “I don’t think God wanted me to have Parkinson’s, but I think God is helping me find ways to find the grace that comes with it. Discovering experientially that you’re not in control can lead to an amazing feeling of liberation,” he says.

There are days when he’s angry or frustrated but at other times, he’s washed in peace.

“The peace comes in the moments I’m symptom-free or I’m in the middle of symptoms and I know they’re not going to last forever. It turns out I do believe in what I preach. Life does come in new ways, like having more time with Jade. God never gives up on finding new possibilities.”

Jade continues her 30-year career as an epidemiologist, now at Mount Sinai Hospital Medical Center in Chicago, and they have more time to spend with their son Jason, a college professor; his wife, Tonya, and their two young daughters. Jade is amazed at how her husband of 31 years has adapted.

“His whole life was based around communication and counseling and teaching and preaching so this is such a huge loss for him,” she says. “Some people might turn bitter or angry or mean and he’s none of those things. He gets discouraged and he feels the pain of the loss, but he’s amazingly resilient and easy to live with.”

Although medication moderates the symptoms, his days are unpredictable. Sometimes there are so few signs of the disease, people ask him if he’s sure he has Parkinson’s. Other times he’s frozen by a lack of mobility or speech. One day at the computer, he felt symptoms coming on. Jade was upstairs and he wanted to tell her, so he tried sending her an e-mail, but his fingers couldn’t find the keys. He decided to write her a note, but his handwriting was illegible. So he headed up the stairs to tell her before stopping, realizing he couldn’t speak.

“When you’ve been talking your whole life, that silence is hard,” he says.

When he prays, he prays for himself, that he can stay true to himself. And he prays for Jade, who doesn’t like to drive but has to drive everywhere now. After he retired on disability in July 2007, they moved to Logan Square, a predominately Hispanic Chicago neighborhood.

Thorn, who remains at the Broadway church as its associate pastor, says the last year has been difficult as she’s worked to support the congregation while dealing with her own grief over losing her mentor.

“He’s left a legacy with us. His ministry was just remarkable. I can’t even call what he gave sacrifices; it was just a way of life for him. He gave what was in his heart and what he felt God called him to do and he did it without exception. Even society could not stop that passion.”

A moment she’ll never forget was watching him during a premarital counseling session with a same-sex couple. One of the men asked him why he would jeopardize his livelihood to marry them. Through tears, he answered, “I don’t know how to do anything different. This is who I am. This is what I’ve been called to do and that’s to minister to all of God’s people.”

All of God’s people, the people he and Jade used to watch from the porch of the parsonage, which sat along a street with modest homes, a dry cleaner, a flower shop. A half hour wouldn’t go by without someone stopping to talk.

“As Jade and I watched this parade of people, these wonderful people, I thought this was what God intended,” he says, as his speech slows. “This is how God made us, all different, so beautiful, a garden of humanity, and we should be able to come together and be who we are.”

His voice stops and tears form. And then he repeats three words, not because of some disease strangling his words, but because of their power.

“Who … we … are.”